Population aging and policy change

We're getting older. In the last 200 years, life expectancy has doubled. [1] By 2050, 1 in 6 people will be 65 or older. That’s 16% of the global population. [2] Meanwhile, the number of babies being born is decreasing. [3] According to the United Nations, "Population aging is poised to become one of the most significant social transformations of the twenty-first century, with implications for nearly all sectors of society." [4]

The need to critically and creatively reflect on population aging is particularly acute in the U.S. Today, as the median age inches toward 40, the U.S. population is older than it ever has been. [5] In 10 years, older Americans are expected to outnumber children for the first time in history. [6] By 2050, the number of Americans 65 and older is projected to increase by 47% and reach 82 million. [7]

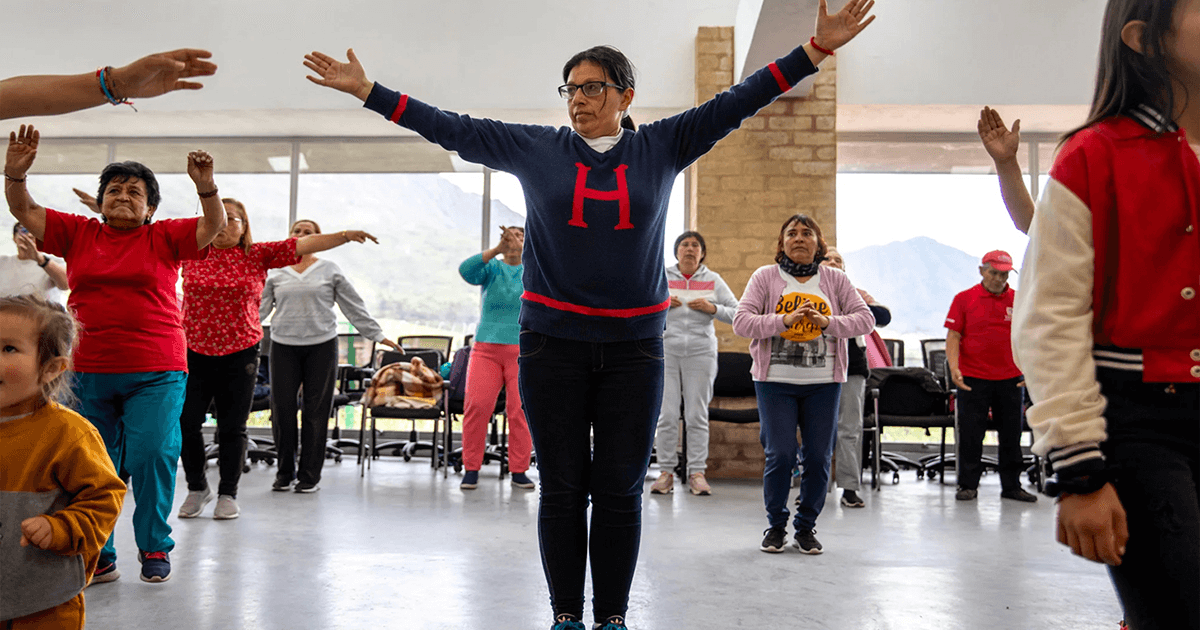

These global trends will have physical, social, economic, and environmental impacts on society and how we age. In response, the United Nations (UN) declared 2021–2030 the Decade of Healthy Aging. [8] And asked the World Health Organization (WHO) to bring together government agencies, nonprofit organizations, academia, the media, and collaborators in the private sector for 10 years of concerted, catalytic, and collaborative global action. [9]

To this end, Public Works Founder Kiersten Matsui teamed up with Lena Blackstock over at Process/Practice Studio. And began exploring different facets of aging in the context of public health – including system design (Vol. 1), service design (Vol. 2), placemaking (Vol. 3), and community development (Vol. 4).

There are signals that suggest healthcare systems as we know them today could look, feel, and operate in radically different ways tomorrow.

As populations age, the need for long-term care will increase. [10] It's hard to imagine how these needs will be met, given many healthcare systems struggle to adequately care for people today. In Canada, Medicare is buckling. [11] In Iran, thousands of healthcare providers are emigrating. [12] In the U.S., hospitals are closing urgent care centers and pausing essential services to survive. [13] And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Yet there are signals that suggest healthcare systems as we know them today could look, feel, and operate in radically different ways tomorrow. Here are two.

Australia’s Aged-Care Legislation

After four years of research into aged care across Australia, the government determined the entire system needed an overhaul. And recommended a new Aged Care Act that 'places older people at the center of all aspects of aged care.' [14, 15, 16]

"Much has been said during our inquiry about the need to ‘place people at the centre’ of all aspects of aged care. To achieve this, we are convinced that a new Act is needed... The new Act must focus on the safety, health and wellbeing of older people and put their needs and preferences first." [14]

Changing rules changes behavior. [17] That's why policy reform is such a powerful leverage point in any system. Yet what we find particularly intriguing about Australia's new Aged Care Act is how they're designing it. The government is co-creating the legislation with older adults, their families, care teams, and advocates like the Aged Care Council of Elders. [18]

Co-creating with the stakeholders for whom a policy, system, or service is being designed has many advantages. It makes stakeholders feel valued, helps ensure the outcome meets or exceeds stakeholders' needs, increases the likelihood of stakeholder adoption, quickly proves or disproves hypotheses, and ultimately, saves time and money.

Oxfam’s Care Policy Scorecard

Measuring impact is an integral yet often overlooked part of the design process. The goal is not to prove that a design – be it a policy, service, or system – works but to improve its capacity to catalyze the desired changes.

Oxfam understands this. The scorecard they designed empowers advocates to track progress on policies that aim to recognize, reduce, redistribute, and represent unpaid care work and adequately reward paid care work. Then, communicate to policymakers what's working, what's not working, and why. [19]